Chain of thought is computation

Framework to understand "thinking" in LLMs, from Dale Schuurmans's keynote at Reinforcement Learning Conference.

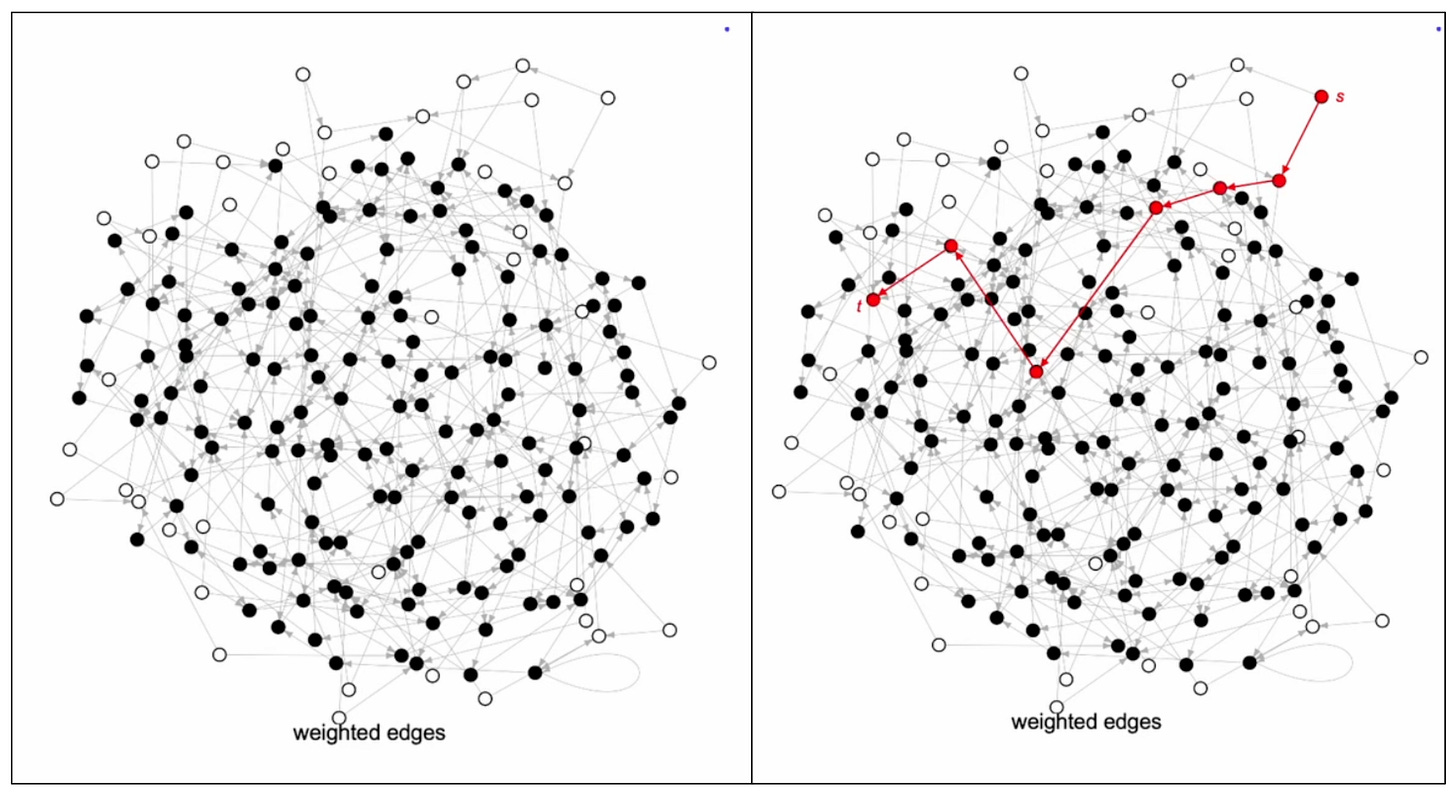

Assume there is a giant directed graph and we were to find the shortest path between node A to node B. If we try to write down the first edge of the optimal path, that would be the hardest edge to choose. We need to know what is the optimal path from second node to node B to choose the first node optimally. Classic dynamic programming. In other words, we must have done most of the computation even before identifying the first edge of the optimal path. This computation scales linearly with the problem size, linear-time computation.

Analogically, if an LLM tries to generate the final answer in one shot, it would have to somehow compress a multi-step computation into a single fixed-depth forward pass (when generating the first token). But if LLMs were to generate a variable size chain of thought before generating an answer, linear-time computation is possible. Chain of thought is computation.

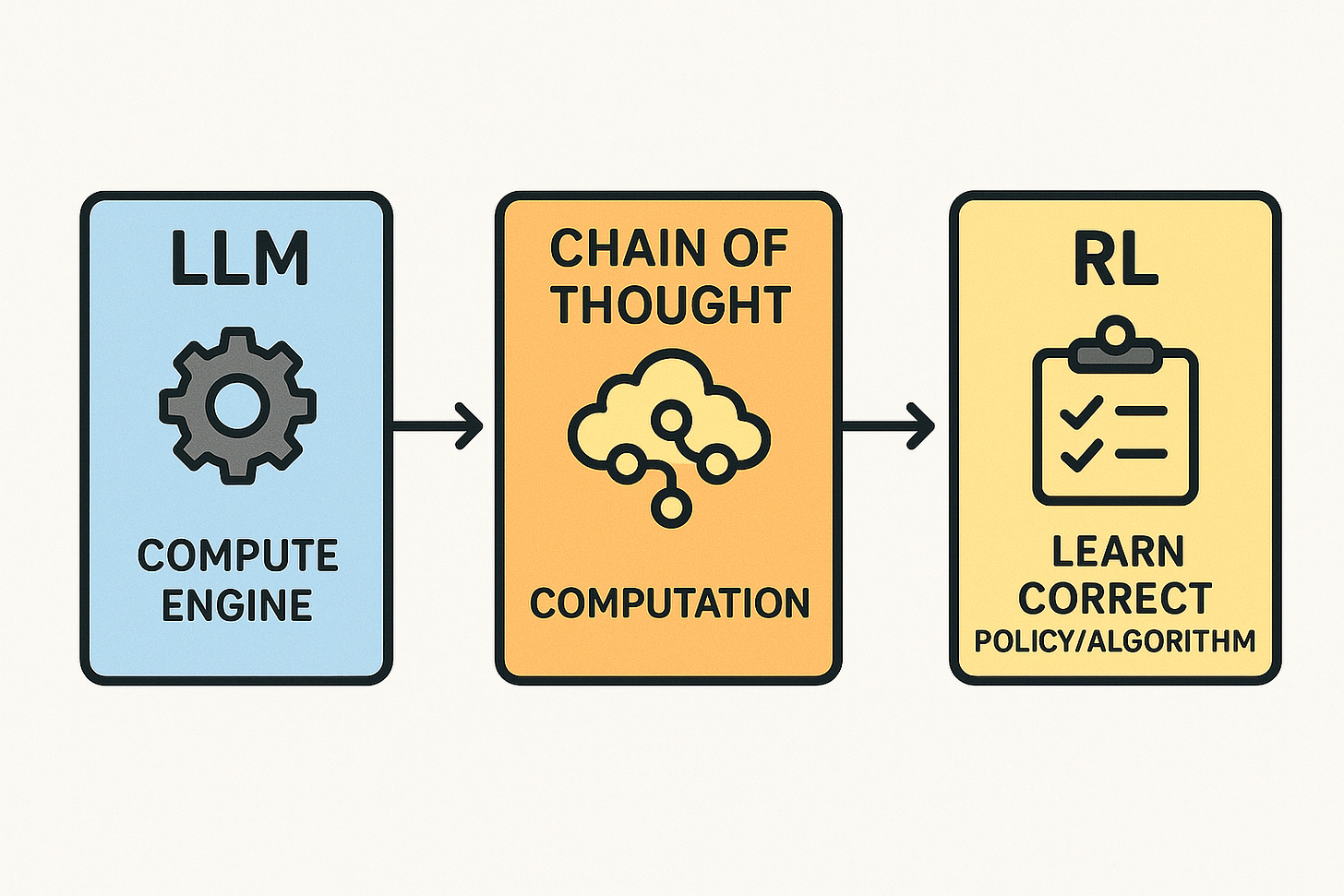

Dale Schuurman (U. Alberta & Google DeepMind, in his keynote at Reinforcement Learning Conference, offered a perspective to understand LLMs as compute engines. Specifically, it explains why chain-of-thought is necessary for reasoning and how it can be treated as computation. This perspective answers core questions like “Can LLMs reason?” and offers a framework for understanding pre-training and post-training in LLMs. It also highlights the inherent limits of learning a formal program from finite data and raises questions about out-of-distribution generalization. The following depicts a characterization of the framework:

Linear-time ≠ one-shot

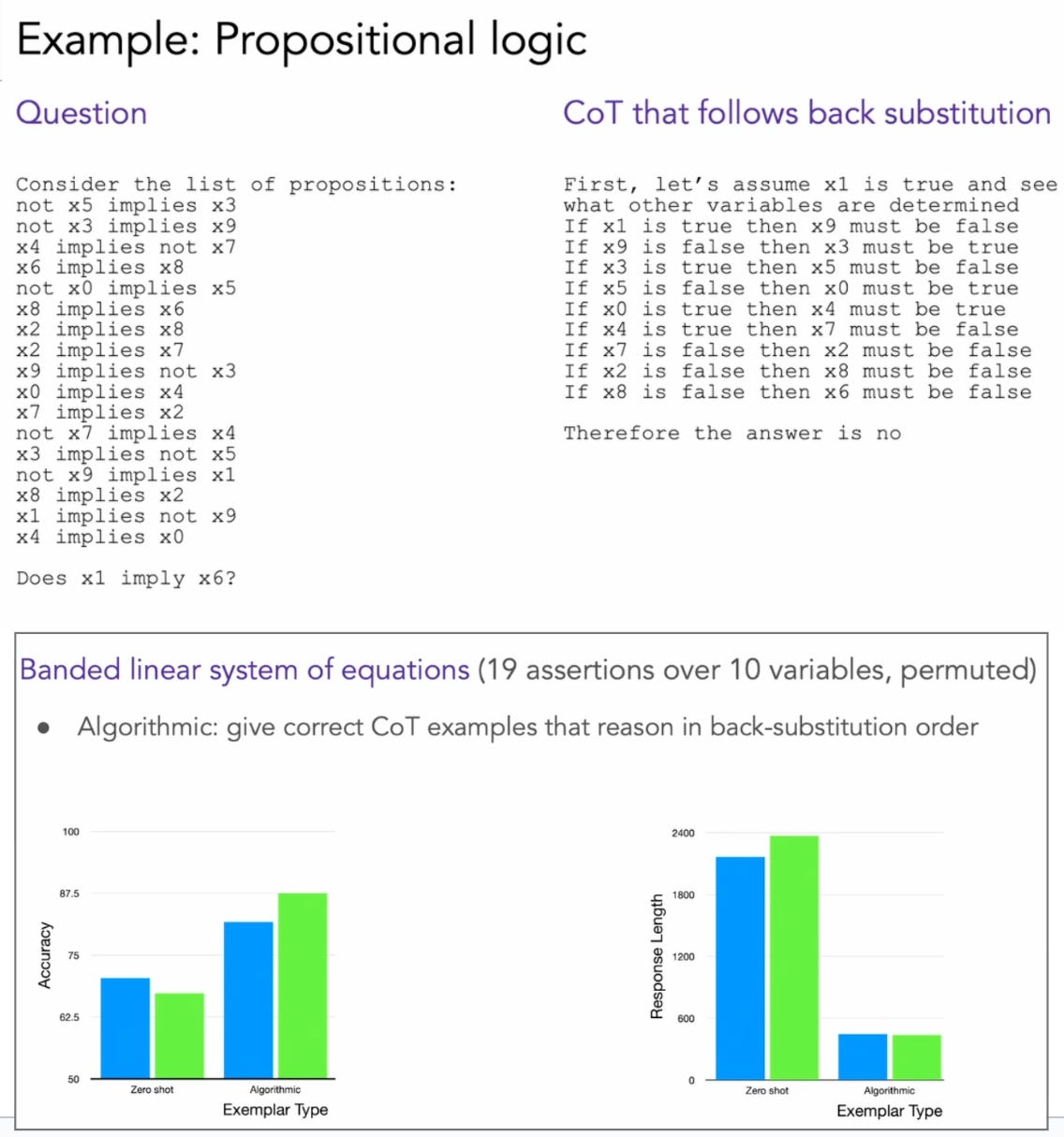

We cannot distill linear-time reasoning into constant-time architectures. As seen above, shortest paths need dynamic programming type of computation and we can’t compress this inherently iterative computation into a single constant-depth forward pass. In a similar case of linear-time computation problem, propositional logic (shown in the below figure), training with CoT that follow back substiution improved the performance considerably above random.

As Dale says, training input-output pairs (without COT) to produce the answer “in one pass” was doomed:

“This cannot work. It’s an impossibility… It’s not a statistical problem. It’s a computer science problem. […] If you want to solve linear-time problems, give the model a budget to express linear-time computations.”

There is an alternative, as seen in NeurIPS 2025 papers, to token-by-token CoT: continuous, latent-space thinking. Instead of reasoning tokens, the model allocates computation inside its vectors.

Reasoning by Superposition: A Theoretical Perspective on Chain of Continuous Thought argues that continuous CoT can encode multiple search frontiers in superposition, enabling something like parallel BFS with fewer explicit steps than discrete CoT. This doesn’t make compute vanish, it changes where the compute lives (in vectors rather than many printed tokens) and shows how a small number of “thinking updates” can still represent multi-path exploration.

Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning proposes iterating a recurrent block at test time, no special CoT data, so the model scales depth as needed (adaptive, budgeted compute) without spitting out long text traces.

Read together, these results pressure-test token CoT by showing that compute doesn’t disappear, it moves: from explicit text to a handful of latent updates. They don’t refute “linear-time ≠ one-shot”; they offer tighter allocation and compression of the required iterative compute.

Pre-training and post-training

If the internet is a giant directed graph, pre-training learns the edges (token-transition statistics). Post-training learns how to traverse the graph for a goal. Schuurmans’s metaphor is crisp: “Pre-training is learning the graph… Post-training is about turning that into a policy that finds paths.” This elicits reasoning which executes the policy learned. Talking about the performance of reasoning models for logical reasoning tasks, this paper says:

“Unlike other LLMs (GPT-4o & DeepSeek V3), R1 shows signs of having learned the underlying reasoning“

Out-of-distribution generalization & Correctness

Even though an LLM is universal in principle, program induction from finite data guarantees there will be inputs just outside what the learned program covers. Schuurmans makes the broader point that machine learning promises are mostly in-distribution, while program execution aims for all instances. If you ignore the difference, you misdiagnose computational failures as “OOD coverage problems.”

Also, how can we characterise CoTs with self-verification & backtracking? Are they verifying the program and choosing a different program to run? Isn’t the case program correctness is undecidable?

There are many interesting questions with this framework of treating LLM as a computer. In Dale Schuurmans’s words:

“machine learning is awesome… but computer science matters… If you ignore those laws, I predict disappointment.”